The music room at Norton Rose Fulbright has panoramic windows looking out over tower bridge and a baby grand piano: an enviable practice room. My friend, Tomyr and I were there to run a workshop on Terry Riley’s In C and discussed how minimalist music has affected our culture. The workshop was part of our work with Music In Offices, an organisation which provides music lessons, choirs, workshops and team building projects to offices around London. Our scratch band was formed of professionals with various musical backgrounds playing: flute, melodeon, djembe, piano, vibraphone and ukulele. In C is one of the most performed pieces of the minimalist era, this owing to the fact that it can be performed by any combination of instruments. The aleatoric element of not knowing who was going to show up to the workshop added to the beauty of it. Our chance combination of instruments made a fascinating sound and one unlike any other performance of In C I’ve heard.

We began the workshop with a performance of Steve Reich’s Clapping Music. The piece demonstrates Reich’s technique of phasing. It also served to illustrate the quintessentially minimalist idea of using minimum resources for the maximum results. There is no variation in pitch, timbre or harmony, just one rhythm being clapped by two people creating five minutes worth of engrossing music. We rehearsed the piece as a group and managed to perform the first few bars together. Tomyr and I had been practising Clapping Music all week in our kitchen and were worried it may be too difficult for participants to join. The participants rose to the challenge. They were happy to try an exercise which even professional musicians are apprehensive of.

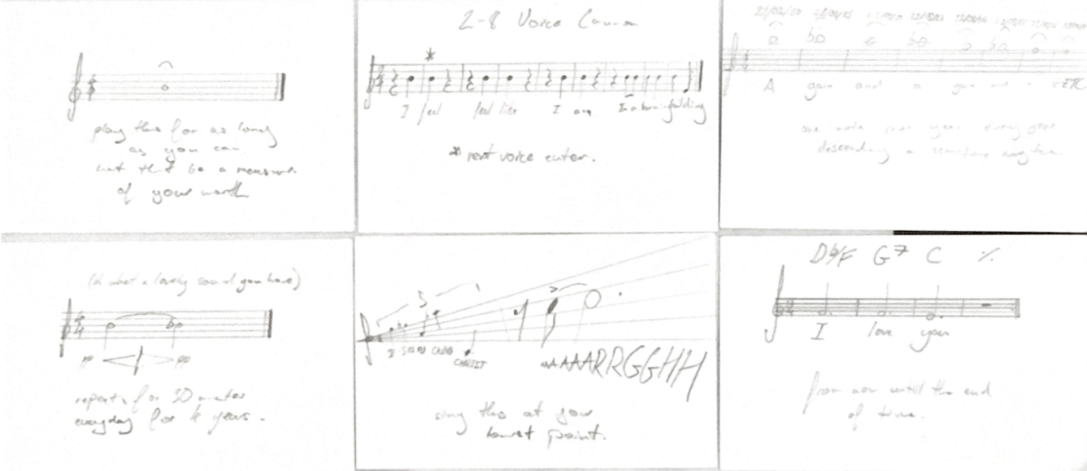

As a sort of musical icebreaker, we played a couple of improvisation games. I invited the participants to play a note within the C major scale for as long as their breath lasts and then change note. Then we improvised short rhythmic cells, still using only notes in C major. Finally, I removed all the rules and we played a brilliant cacophony for 5 minutes. I was overjoyed at the confidence with which the participants performed these improvisations. When I was a student at Guildhall a professor asked us to try these same games as an introduction to jazz improvisation. When they shouted “go!” there was a solid 30 seconds of silence, 30 seconds worth of visceral self-consciousness. A group full of students who do nothing but play music were so concerned that they may play the ‘wrong’ thing that they didn’t play at all. I expected the same muted response in our In C workshop. I had a stock speech about it being impossible to be wrong and how Miles Davis would play the ‘wrong’ note so confidently that it would become the ‘right note’. In the end, I didn’t need to encourage them to think ‘what would Miles Davis do?’ because they played confidently right from the start.

This made me think about the differences between a group of music students at Guildhall and a group of office professionals at Norton Rose Fulbright. One obvious distinction is technical proficiency: students will be more in tune, more rhythmically precise and quicker to sight-read parts. Beyond this distinction, the line is a lot more blurred than I first thought. You may think a music student would have more contextual knowledge allowing for a well-informed interpretation of a piece but many times my adult students have demonstrated a far more comprehensive knowledge of music history than me. You may think that someone who has dedicated their whole life to music may have some intense love for music which would shine through in their performances but within that assumption lies a difficult question: do music students love music more than adult amateurs? People have all sorts of ulterior motives for learning music: children learn to help them make friends, teenagers take grade exams so their UCAS applications look good, professional musicians often perform just for money’s sake. For adult amateurs the motivations are different, there are less social pressures to learn. An adult is free from entrance exams, pushy parents and school concerts. Often, I get the sense that my pupils love music as much or even more than me and my colleagues. They are playing music for music’s sake, without ulterior motive and that’s a beautiful thing.

We worked through the 36 cells of In C and then prepared for a full performance. Our final rendition took about 10 minutes to perform and was by all measures a great success. With that, there was no line between professional and amateur. This was not a good performance for a group of amateurs but simply a good performance. Amongst styles of music, classical music is unique in its desire for technical perfection. This stems from the need to correctly realise a composer’s instructions: in jazz, folk or pop music the instructions are rarely as strict and the performer takes more ownership of what they perform. Classical performances (even when performed by professional musicians) are often totally dismissed if they’re not immaculate. One need look no further than the youtube comments beneath Barenboim’s performance at Jaques Chirac’s funeral service to see how offended people become from a couple of missed notes.

I see our performance of In C as proof that perfection is not necessary for a successful classical performance. Confidence, intrigue and open-mindedness are far more important for the rehearsal and performance process.