Music and (Prescription) Drugs

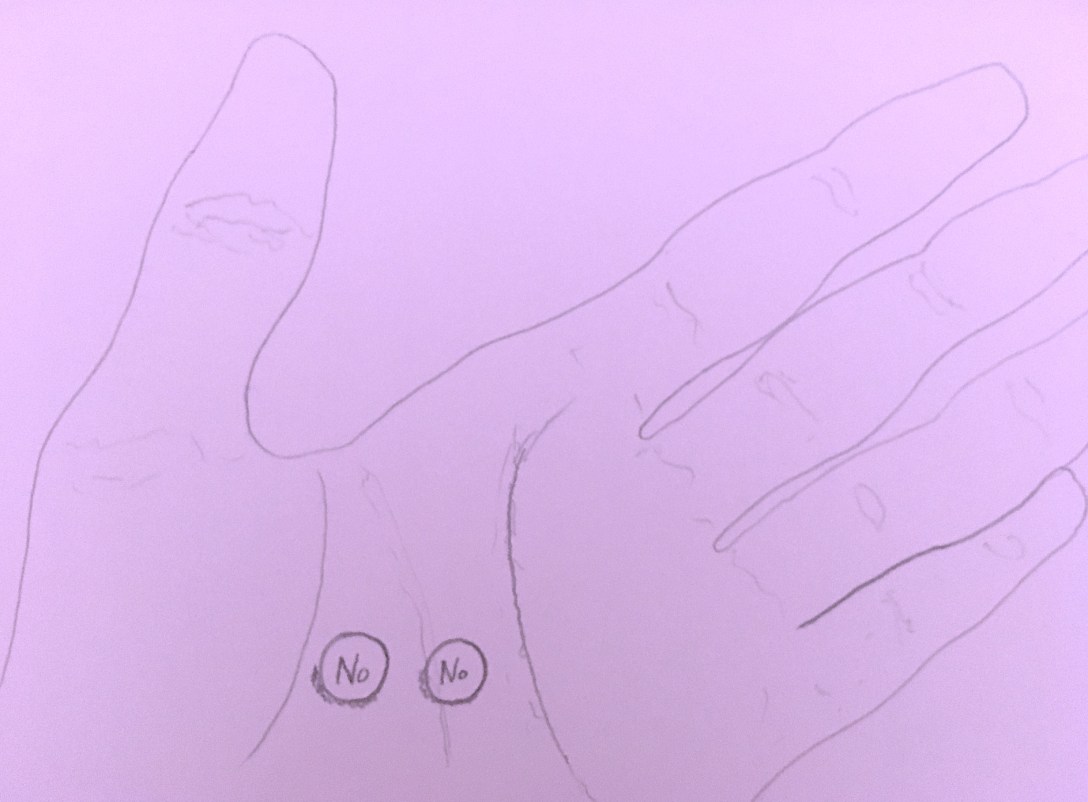

Engraved in each Nortriptyline tablet is the abbreviation ‘No’ and each night before taking my dose I am confronted with the short message ‘No No’. I am afraid of these drugs but I can mitigate this fear with intrigue. Musical composition is as much a mystery to neurologists as my chronic migraine. I have the unique opportunity to observe the effects of my drugs on the generative process. My creative output can function as a diary charting the effects of my various medications.

My neurologist was surprised when I said I wasn’t taking any recreational drugs or binge drinking. He said I wasn’t fulfilling the stereotype of a musician that he had in his head. There is a strong association between drugs and music. People often attribute incredible feats of creativity to drugs rather than individuals. It is understandable that someone would believe that David Bowie could only create what he did with superhuman creativity induced by various recreational drugs. If we don’t attribute creativity to drugs it is often attributed to mental illness, particularly in classical music. It is easier for people to believe that Schubert’s prolific output in his final years was the result of a syphilitic madness rather than an incredible man composing regardless of his deteriorating health. These myths come from the average person’s desperate desire to be Bowie or Schubert. It is easier to believe that creativity is the result of exceptional circumstances rather than intense practice. Thus we can believe that one day some drug or madness will take over us and we’ll rise to their level. If I believed that heroin or syphilis would allow me to create music on par with Bowie and Schubert then I would consider it. I know a lot of people (who adore music and would do anything for it) who would join me in my heroin binge.

The side effects of my medication and the effects of my chronic migraine are often indiscernible. Both cause nausea, confusion, and a general feeling that your senses can’t quite be trusted. From a creative perspective, this is an upside. The mental state that leaves you wondering up and down supermarket aisles without a full understanding of where you are is also the state that allows you to write music without judging yourself too harshly. I suppose a similar state could be induced by a bit of heroin or a syphilitic madness. Music feels like something ungrounded in the empirical world; when the walls start moving you can feel closer to music than the ground beneath your feet.

Both propranolol and naproxen induce nightmares. What is more creative than a nightmare? Something so real yet abstract, where you function as director, actor, audience, stage designer, producer, and composer. However bizarre or vivid nightmares are they are yet to help me produce anything. As we all know, dreams are quickly forgotten and attempts to capture them in writing often feel pale. There are stories of composers leaping from their sleep to write down a theme like Elgar after having his tonsils removed scribbling down the first theme of his cello concerto, but I have had no such luck.

Salvador Dali, Max Ernst, Rene Magritte, and all their surrealist contemporaries aimed to reveal the unconscious. Some of them did so by painting their dreams. Ernst allows one to stare at a dream for as long as they like without its details fading as one’s own dreams do. Surrealist art has a solid place in popular culture (with Dali’s melting clocks as its mascot) but surrealist music hasn’t been quite as successful. Although one of the first works to be described as surreal was Satie’s ballet Parade, the music of the movement was vastly overshadowed by the visual art. Ultimately, I think this is down to the fact that the subconscious is far more visual than musical. At least in my case, a dream can leave vivid images but has never left vivid sounds. Max Ernst’s L’Ange du Foyer looks like an image I have seen in a nightmare; Satie’s Parade doesn’t sound anything like my dreams. This is, of course, just my experience and your brain may conjure up great tunes in your sleep: write them down because I’d love to hear them.

The concrete effects of my migraine on my music are vague. It would be difficult to see a distinction between migraine music and healthy music. Around January 2019 I was as ill as I’ve ever been. I was on a collection of medication that I now believe was having no positive effect. All I wanted to do was write a pretty, romantic piano sonata whilst a year before (when I was perfectly healthy) I was writing horrible stabbing atonal music for 8 saxophones and piano. These were merely the projects I was most focused on at the time: I was still trying to write pretty music in 2018 and I was still writing horrible stabby music in 2019. I’m sure if I was a better music analyst I would be able to find some polarising distinction between my migraine music and healthy music but the fact that the difference is not clear on the surface means it’s probably inconsequential.

I find it bizarre that all the chemicals in my brain could have gone through such instability but the things I have created have not changed at all. It is reassuring that something unshakeable remains: an identity that no illness can take away.